nC2 worked with the International Maritime Pilots’ Association (IMPA), providing the evidence they needed to improve safety practices for pilots and other seafarers worldwide.

Pilot ladders

A pilot ladder in use. Photo: Capt. Arie Palmers, Nederlands Loodswezen

The project focused on a simple piece of equipment with a crucial role – the pilot ladder. Captain John Pearn, an experienced pilot and IMPA’s Associate Advisor on Safety Projects, explains: “Ports and waterways around the world have pilots, who are skilled mariners with expert knowledge of local tides, depths and procedures. When a ship arrives at the pilot boarding station, the pilot will board it and direct navigation into the harbour, through the canal or along the river.”

To get on board, they use a pilot ladder – a specific type of rope ladder with wooden steps – which is rigged to allow the pilot to climb up and down the side of the ship. These ladders are secured to a fixed point on the deck, but the length of the ladder will vary depending on how high or low the ship is in the water. However, while there are regulations and industry standards that set out the required features of the pilot ladder and what is required for a safe pilot transfer, there was no requirement or recommendation addressing how to secure the pilot ladder to the deck when the full length of the ladder is not required.

Securing a pilot ladder can be done in different ways, and IMPA asked us to find out which method was safest. As well as resolving a longstanding debate in the industry, the evidence will be used to drive improvements in international safety standards.

As Nick Cutmore, Senior Advisor for IMPA says: “The nC2 project is the first appliance of science to this topic. Put simply, it’s about avoiding accidents and saving lives.”

Professor Nicola Symonds, Director of nC2, adds: “We were delighted to work with IMPA and play a part in improving safety for pilots, seafarers and other users of pilot ladders around the world.”

Putting safety first

Unfortunately, ladder-related safety incidents are not uncommon, and they can be deadly, as Matthew Williams, IMPA’s Secretary General, explains: “This year we’ve already lost four pilots. Not all of these incidents related to how the ladders were tied off, but our annual safety campaign and survey results indicate that the safety culture around pilot transfer arrangements needs to be continually reinforced and revitalised.”

During his 31-year career, John has had his own share of close calls and is keen for the industry to take on evidence-based advice on better practices. “I’ve been on ladders that have slipped because they haven’t been properly secured,” he says. “There was even one occasion when I climbed 6 or 7 metres to find two seamen standing on the ladder to hold it up!”

John adds: “There are many causes for failed pilot ladders, so this isn’t about blaming seafarers. It’s about learning and providing evidence-based solutions rather than simply relying on long-held opinions.”

Driving regulatory change

IMPA has an opportunity to deliver change as a result of the decision by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) to revisit the regulations and recommendations for pilot transfer arrangements. Their goal is the inclusion of enhanced requirements in a new mandatory performance standard associated with SOLAS (International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, 1974), chapter 5, regulation 23.

A pilot ladder in position. Photo: Capt. Arie Palmers, Nederlands Loodswezen

However, with many issues competing for attention, the IMPA team needed robust data to make their case. Nick says: “It has taken years to bring this issue to the table, so we want to come armed with scientific evidence to demonstrate why one method is better.”

That’s where nC2 came in. “We have to bring our members and the wider shipping community with us,” says Nick. “They will be able to see nC2’s results, and the footage of the tests, and see that this was a job done properly.”

Knots or D-shackles?

The traditional way to make a pilot ladder fast is to tie it off with ropes, using seamen’s knots on the ladder’s side ropes. However, over the years, the use of metal D-shackles to secure ladders has also become common.

John explains: “Opinions differ about which method is best. There’s a perception that standards of seamanship are not as high as they used to be, so a metal shackle will be more secure than a knot that may not be properly tied. But there’s also a concern that using a shackle puts all the pilot’s weight on the step or other fixings of the ladder, rather than the side ropes. The breaking strain of the step isn’t as high as the breaking strain of the side ropes. On top of that, you’re potentially putting extreme force in the same place each time, which could lead to localised damage to the ladder.”

Providing the evidence base

To resolve the question, the nC2 team devised a series of mechanical tests to establish the baseline characteristics of the ladder components, what happens when the ladder is secured and used, and the potential failure mechanisms. Nicola explains: “It’s not something you can easily model on a computer because of the complex interactions between the different materials, loads and forces at play – it had to be done empirically.”

The project involved three work packages.

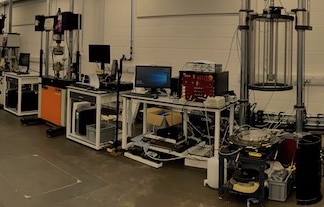

Dr Benjamin Cunningham conducting tensile tests

Work package 1: Tensile testing

First, we sought to understand the overall strength and behaviour of the elements of the ladder, for example pulling sections of plain rope, knotted rope and rope with sections of step, to get a baseline.

Work package 2: Tensile testing with a focus on wear (‘slip and grip’)

Ropes were tied to the ladder side ropes and dragged down to see how much they gripped and how much they slid, using different types of rope, different knots and a strop (a short rope with loops).

Work package 3: Wear test applying cyclic tension

We set up a jig that equated to the ladder being secured with a metal D-shackle and applied a series of loads to simulate the ladder being thrown out, a person getting on, climbing 10 steps up and 10 steps down, getting off, and the ladder being pulled away. This was done with two different sizes of D-shackle and repeated 1,500 times on multiple variations of the rope conditions, to simulate approximately two years of in-service wear.

As with many of our projects, the tests were bespoke, which meant fabricating additional components and modifying the test machines. Matthew comments: “None of this was a problem and they took it all in their stride. There was never any barrier to us going as far as we wanted with the work.”

Professor Nicola Symonds presenting at the 2024 IMPA conference

In April 2024 Nicola was invited to present the results to pilots and other representatives of the maritime industry from around the world at the IMPA Congress in Rotterdam.

Big-picture benefits

Maritime pilots deliver an essential public service for navigation safety, marine pollution prevention and maritime trade efficiency. They can only deliver this service if they can get safely on and off ships. “The ladder is a small tactical piece of an important job: getting a hugely valuable asset on board to deliver the social purpose that is pilotage,” says Matthew. “The alternative – transfer by helicopter – carries its own challenges.”

And improved safety guidance won’t just benefit pilots, as Matthew explains: “Pilots are just one set of users. There are seafarers, flag State inspectors, vetting inspectors, classification society surveyors, and many others who board ships during their work.”

Working in partnership

The IMPA team knew they wanted the scientific rigour associated with a university-linked consultancy. A visit to nC2’s labs and a discussion of the brief reassured them that we could provide the expertise they needed.

“We were impressed with the facilities and with the evident depth of nC2’s understanding of materials,” adds Matthew. “It was clear that Ben [Dr Benjamin Cunningham, nC2’s mechanical test consultant] was listening to our discussions carefully to make sure the tests he designed would be fit for purpose. That attention to detail was really impressive, and we’re very confident in the results.”